Final Reflections by Brandon Woods

I have traveled over 40,000 miles around the world. I have hiked up hills in Nepal and watched the sun rise from behind the Himalayas. I have climbed the great wall, ridden motorcycles in Papua, surfed in Bali, hiked through fields with a Monk in Thailand, swung on vines through ruined temples in Cambodia, gotten robbed in Nepal, ridden trains through India from the top to the bottom, slept in an airport in Turkey, dined with local friends in Rome and Madrid, and slept on a boat in northern Spain. And now I am home.

Re-entry into America came three days before my family celebrated Christmas, which was on December 23rd. For four and a half months everything I needed fit into an 80-liter bag on my back. Christmas morning arrived, and I opened one gift after another until I sat surrounded by a pile of things meant merely for pleasure rather than necessity. It felt vain.

The next day my mom’s side of the family paraded into my parents’ home in San Luis Obispo to celebrate the real day of Christ’s birth. My older sisters remarked, “Brandon, I don’t think you have laughed since you got home,” which pretty much summed up my emotional state during that first week.

Soon the Christmas hype faded, which gave me time to sit and process the emotions I experienced as I transitioned from the Third World to Christmas in America. After almost two weeks of solitude the reflection process took a turn—it was now time to make videos and slide shows for presentations at Grace Church in SLO. For two and a half days Tyler and I sat side by side at our computers searching through 7,000 pictures and 20 gigabytes of video for usable material. Tyler’s goal was to make a 15-minute video, to show the people and climate of each country. I, on the other hand, put together a photomontage of essentially the same thing—I got the easier task.

We first showed the video to a high school youth group. As the film rolled, I sat and enjoyed listening to the groans and peals of laugher that came from the high school students as they viewed some of the food we ate and the situations we experienced. All at once the entirety of my adventure fully hit me. Prior to that moment I always knew my experience was unique, but this was the first time I was able to look at the trip objectively as a whole rather than in segmented parts.

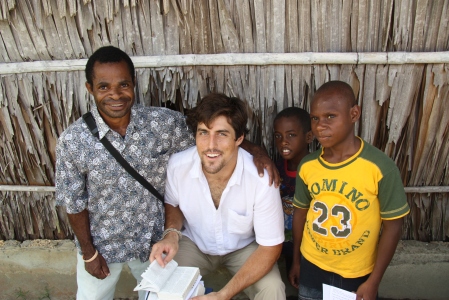

Despite all of the people I met and the places I saw, all of the events and memories, I consider them menial compared to the ways God changed my heart and revealed His global church. The times Tyler and I enjoyed most were when God showed us something new about His Character and His Kingdom. Whether we were sitting in a house church in Bali or visiting a small group of women involved in microfinance, we felt God teaching us that community is crucial to Christ’s great commission.

A friend, DJ Bigbie of Crossroads International in Hong Kong, brought our attention to the relationship between community and the great commission. Once we entered Indonesia, we started to fully experience this relationship. We saw community served as a conduit for sharing the person of Christ. The idea itself doesn’t seem that complex or innovative. But one night in Indonesia we realized how different it is from the way most Western Christians go about sharing their faith.

The night I am referencing took place on the island of Bali. Tyler and I were invited to go to a small group meeting with a bunch of punk rock kids. The meeting place was a Circle K parking lot. We brought a few recovering drug addicts with HIV from the group home where we had been living, and our translator, Chris. We were late and all of the punk kids were seated in a circle eating some rice with pulled pork and hot sauce wrapped in banana leaves. After grabbing a drink and a king-sized Butterfinger, I joined the circle.

All of the kids there didn’t go to a regular church. This meeting outside the Circle K was church. Luckily for us, about half of the local kids spoke decent English and one kid, named Chris, (not Chris the translator) explained their situation to us. He told us that traditional, or Western churches, rejected them because of their Mohawks and tattoos. So, they decided to start their own interest based house churches. The goal: to create a group of people brought together by a common interest. According to their house church philosophy, a relationship must be established before any evangelism takes place.

That night was especially convicting to me. In high school when I wanted to share the Gospel with friends my first action was to invite them to Youth Group. In my mind, my involvement stopped there; I hoped the pastor would preach about the sin of man and the grace of God, leading any friend towards repentance. I do not think that my actions in high school were abnormal. I think that Western Christianity’s attempt to preach the gospel has been reduced to an invitation to a church function and an expectation that the church will do the rest.

But what we should ask ourselves is this: why would any non-Christian want to come to Church? Sure, they may feel like something is missing from their life, but more often then not once at Church they will most likely feel like they do not fit in, especially for the younger generation. Whether we like it or not, there is an underlying pressure in Western Christianity to look, act, and talk a certain way. Chances are, if I have sleeve tattoos, smoke two packs a day, and like to drop an occasional curse word, I will not feel comfortable going to a Church composed of prim and proper white people who use words like redeemed and sanctified.

I think that the punk kids have it right. After all, isn’t the Gospel about meeting people where they are, introducing them to Christ, and then allowing Christ to transform their lives? Paul did that. In Acts 17: 22-23 when Paul addresses the Athenians, He says:

“Men of Athens! I see that in every way you are very religious. For as I walked around and looked carefully at your objects of worship, I even found an alter with the inscription: TO AN UNKNOWN GOD. Now what you worship as something unknown I am going to proclaim to you.”

Paul creates community with the Athenians by meeting with them at the center of their society—the forum—and appeals to their own form of religion creating a way of introducing the God of the Bible.

Tyler and I experienced this method of sharing the Gospel all over Asia. We went to break dancing house churches, 50% of which were Muslim; we lived in a group home for drug addicts and orphans, and volunteered at a microfinance firm. The more we saw the relationship between community and the gospel, the more we realized that the furthermost people from God’s kingdom come when we meet them where they are, not from a place where we are comfortable.

There are a lot more things that God showed us through out our travels, but I think I will stop here. If you would like to hear about some of the other things I learned, please feel free to contact me. Thank you all so much for partnering with us as we traveled around the world. We pray that our experiences Asia will continue to shape our thoughts and actions for a long time to come. Thank you, and God Bless.